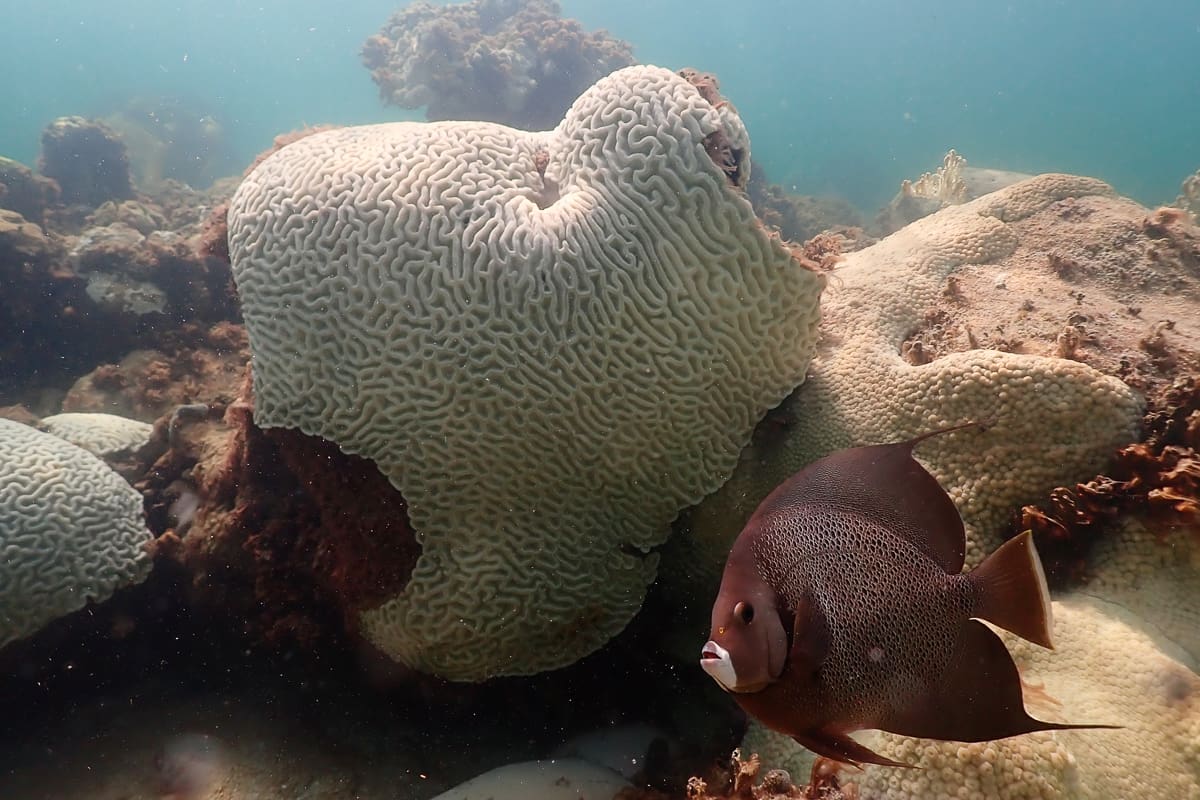

It’s been a disastrous year for corals off the coast of South Florida as record sea temperatures caused widespread bleaching. But researchers at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School reported some good news in January.

They discovered for the first time a single-celled microbe can help corals survive ocean-warming events like bleaching. The new study offers new information on the role microbes might play in helping corals withstand end-of-century warming projections, according to a news release.

These findings have important implications for corals across the globe as they face more frequent ocean warming events, scientists say.

“This is the first time that a non-algae microbe has been shown to influence the ability of corals to survive a heat-stress event,” said the study’s senior author Javier del Campo, an adjunct assistant professor at the Rosenstiel School.

“As corals face more and more heat-stress events due to climate change, a better understanding of all the microbes that may influence survivability can inform conservation practitioners as to which corals they should prioritize for intervention.”

Researchers found that the abundance of certain protists within the coral microbiome — the diverse microorganisms that live within corals — can inform scientists as to whether a coral will survive heat stress.

To conduct the study, an international team of researchers collected coral samples from across the Mediterranean to analyze their microbiome and conduct heat-stress experiments.

They found that a group of parasitic single-celled microbes are more common in corals that survive heat-stress. “The microbiome is a vital component of coral host health and we should study all members of it,” said del Campo.

In another research project led by Rosenstiel scientists, a team found South Florida’s near-shore reefs are less vulnerable to ocean acidification. The results offer a glimmer of hope as climate change impacts coral reefs worldwide, according to a Rosenstiel news release.

Ocean acidification is a major climate-related threat to coral reefs as ocean waters absorb more atmospheric CO2 from the burning of fossil fuels.

“In contrast to many regions globally where ocean acidification is being exacerbated, we found that South Florida’s inshore reefs — and sheltered areas that coexist with seagrass communities — are being buffered from the negative effects of acidification,” said the study’s lead author Ana Palacio-Castro, a researcher at the Rosenstiel School-based NOAA Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies.

Seawater turns more acidic as the ocean absorbs atmospheric carbon dioxide, which results in a drop in pH level. This can affect corals from building and maintaining their calcium-based shells and skeletons. Acidification can ultimately compromise the structural integrity of coral reefs and the marine life that rely on them.

The researchers analyzed 10 years of continuous seawater samples collected at 38 monitoring stations across the Florida Reef Tract.

“The findings underscore the importance of local monitoring to understand how ocean acidification is impacting our region and to identify potential acidification hotspots and refugia,” said Palacio-Castro.

Invest in Local News for Your Town. Your Gift is tax-deductible