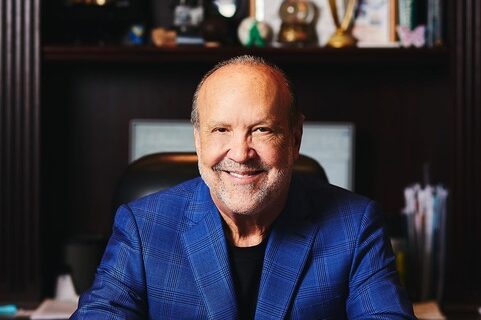

Ron Book, chair of the Miami-Dade County Homeless Trust, says he is “cautiously supportive” of the new law that will ban Florida’s homeless from living on public sidewalks and parks but with promises of services for substance abuse and mental health.

But Book said that Miami-Dade County won’t be obligated to initiate encampments, as envisioned under the new law, because of the Homeless Trust’s “continuium of care” which works to find permanent housing for those living on the street.

“In Miami-Dade County, our focus is and will remain on permanent housing and comprehensive services with the goal of ending homelessness, not managing it,” Book said.

The Unauthorized Public Camping and Public Sleeping law, signed by Gov. Ron De Santis on Miami Beach Wednesday, is a civil approach for communties that have no strategy to address homelessness, he said.

“This bill has funding mechanisms in place to incentivize communities to have a plan, leadership and financial support to do the work, which is the model used by Miami-Dade County,” Book said. “We hope to be at the table to offer our expertise and insight.”

The state Department of Children and Families would oversee local governments that set up designated areas for the homeless to camp for up to a year under the new law, which takes effect Oct. 1. Anyone using those encampments would be prohibited from using alcohol or illegal drugs, with sanitation and security to be provided.

Beginning in January 2025, the law will allow residents, local business owners and the state attorney general to file a lawsuit to stop any city or county from allowing the homeless to camp or sleep on public property.

“If you are going to ban this, we need to offer shelter, we need to offer a reasonable place to stay, a place with dignity,” said Narcisco Munoz, whose group, Key Biscayne-based Hermanos de la Calle, does homeless outreach and works closely with the Homeless Trust.

He said it is important to note that these tent cities, such as as one around Miami’s Downtown Medical Center, are communities and those living on the street will need time to prepare. “They have their whole life there,” Munoz said. “This is vulnerable population.”

The homeless population in Miami is far from homogenous, Munoz said. There are those who are living in their cars because they can’t afford rent, others who went bankrupt because of a medical condition, those addicted to alcohol and drugs, the mentally ill and the chronic homeless who choose to to live on the street.

“Many are not there because they want to be there, but they are there because of the lottery of life,” he said.

It remains to be seen if any of these groups will not move to a designated encampment — especially one where drugs and alcohol are prohibited.

“This would address this issue that has plagued communities across the country where these homeless camps overwhelm just the quality of life,” said DeSantis, coming off a third-place showing in his own state for the Republican presidential nomination in Tuesday’s primary election.

Opponents say the bill is about keeping the homeless out of site, out of mind.

“This bill does not and it will not address the more pressing and root cause of homelessness,” said Democratic state Sen. Shevrin Jones during a debate this year. “We are literally reshuffling the visibility of unhoused individuals with no exit strategy for people who are experiencing homelessness.”

Read: Homeless Holiday. On the Miami streets with Hermanos de la Calle

The encampments would be created if local homeless shelters reach maximum capacity, according a news release from the governor’s office. The law requires regional entities to provide necessary behavioral treatment access as a condition of a county or city creating an encampment.

Allowing the homeless to camp in public spaces affects the local quality of life, can be a nuisance for businesses and makes it more difficult to deliver them needed services because they’re scattered, DeSantis and other supporters of the measure said.

“I think this is absolutely the right balance to strike,” DeSantis said. “We want to make sure we put public safety above all else.”

During the Legislature’s latest session, Florida’s homeless population was estimated to be about 30,700 in 2023. That’s a fraction of the homeless populations in many large U.S. cities, but the law’s sponsors said it could worsen because of Florida’s rapid population growth.

“This bill will not eliminate homelessness. But it is a start,” said Republican state Rep. Sam Garrison. “And it states clearly that in Florida, our public spaces are worth fighting for.”

DeSantis, however, said the new law is a unique approach in pledging to provide the services that homeless people often need.

“This is going to require that the services are there to help people get back on their feet,” the governor said. “I think it’s important that we maintain the quality of life for the citizens of Florida.”

Editor’s Note: This story updates a previous version with comments from Ron Book, chair of the Miami Homeless Trust. Curt Anderson, reporter for the Associated Press, contributed to this article.

JOHN PACENTI is a correspondent of the Key Biscayne Independent. John has worked for The Associated Press, the Palm Beach Post, Daily Business Review, and WPTV-TV.